When designing a house, most people focus on plans, elevations, and finishes—but the real safety of a building lies in how accurately its loads are calculated and transferred to the ground. A small mistake in load calculation can lead to under‑reinforced members, excessive deflection, or unnecessary overdesign that wastes steel and concrete.

Imagine a G+1 family house where the slab thickness was assumed blindly without calculating the dead load and live load coming on each beam. The structure might “look” safe on drawings, but without proper load calculation for the residential building, cracks and serviceability problems may appear after occupancy. This guide walks through the basics of load calculation step by step so that slabs, beams, and columns are designed on firm ground.

What is a load in a residential building?

In structural engineering, a load is any force applied to a building that the structure must safely resist throughout its life. For residential buildings, loads are broadly divided into vertical gravity loads (dead and live) and lateral loads (wind and earthquake).

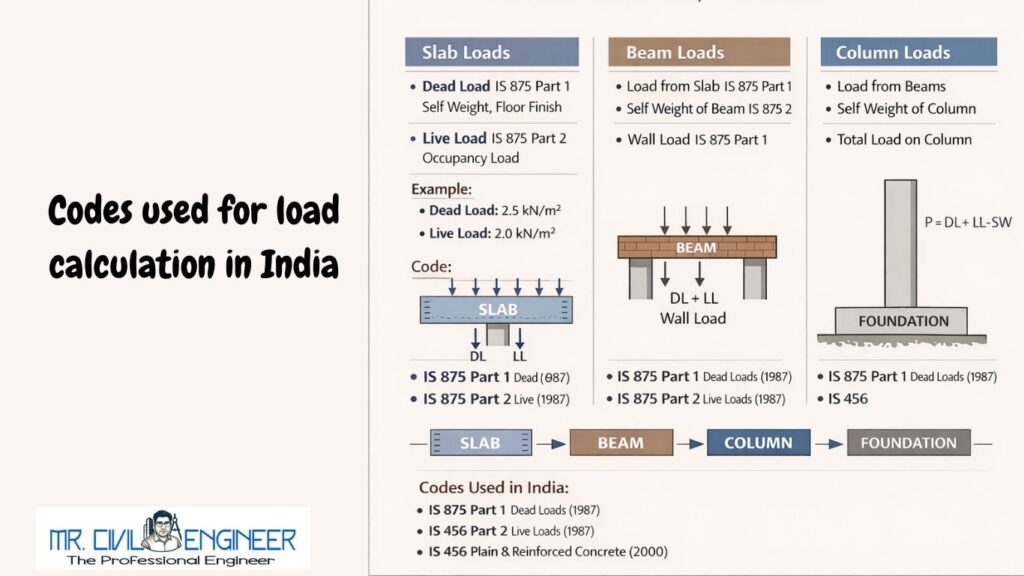

Every structure follows a load path: loads first act on slabs, then are transferred to beams, beams pass them to columns, and finally columns transfer them to footings and soil. Understanding this load path is essential because load calculation for each element depends on how it receives and distributes the forces.

Main types of loads on residential buildings

For typical low-rise houses, the most important loads are:

- Dead loads

- Self-weight of RCC slabs, beams, columns.

- Masonry walls, plaster, floor finishes, tiles, parapets.

- Live loads (imposed loads)

- People, furniture, movable partitions, water in overhead tanks, etc.

- Environmental loads

- Wind load, especially for taller or exposed buildings.

- Seismic (earthquake) load, particularly in earthquake-prone zones.

Snow, temperature, and other special loads are considered in specific regions or special cases, but for many Indian residential projects, gravity and seismic loads dominate.

Codes used for load calculation in India

For Indian residential buildings, structural engineers rely on a set of IS codes:

- IS 875 (Part 1) – Code of practice for design loads: dead loads.

- Gives unit weights for materials like concrete, brick, tiles, plaster, etc.

- IS 875 (Part 2) – Imposed loads (live loads).

- Specifies recommended live load values in kN/m² for different occupancies (rooms, corridors, roofs, stairs).

- IS 875 (Part 3) – Wind loads.

- Used to calculate design wind pressure and resulting forces.

- IS 1893 – Criteria for earthquake-resistant design of structures.

- Provides methods to compute design seismic base shear and its distribution.

Any manual load calculation for a residential building should align with these code values for unit weights and live loads.

Step-by-step dead load calculation for a slab

To understand dead load calculation, consider a typical RCC slab in a bedroom.

Assume:

- Slab thickness = 150 mm = 0.15 m.

- Density of reinforced concrete ≈ 25 kN/m³ (typical from IS 875 Part 1).

- Floor finish (tiles, mortar) ≈ 1.0–1.5 kN/m².

- Ceiling plaster ≈ 0.3 kN/m².

Dead load of slab per m²:

- Self-weight of slab = 0.15 × 25 = 3.75 kN/m².

- Add floor finish = say 1.2 kN/m².

- Add ceiling plaster = 0.3 kN/m².

Total dead load on floor slab ≈ 3.75 + 1.2 + 0.3 = 5.25 kN/m².

This value is then used as uniformly distributed load on the slab during analysis.

Dead load of walls, beams, and other components

Wall load

For a 230 mm thick brick masonry wall with plaster on both sides:

Assume:

- Wall thickness = 0.23 m (brick) + 0.035 m plaster (both sides total) = 0.265 m.

- Wall clear height = 3.2 m with 0.4 m deducted for openings, effective ≈ 2.8 m.

- Density of brick masonry ≈ 20 kN/m³.

Wall load per meter run = 20 × 0.265 × 2.8 ≈ 14.8 kN/m.

This line load is applied on the supporting beam(s) below the wall.

Beam and column self-weight

For a beam with width 0.23 m and depth 0.45 m, density 25 kN/m³:

- Self-weight = 0.23 × 0.45 × 25 ≈ 2.59 kN/m.

Similarly, column self-weight can be estimated using its cross-sectional area and height.

These dead loads are added to the slab and wall loads when evaluating total load on each structural member.

Live load for residential buildings

Live load represents the variable occupancy load due to people, furniture, and movable items. IS 875 (Part 2) specifies typical live load values for different spaces in residential buildings.

For example (typical ranges):

- Bedrooms, living rooms: around 2.0 kN/m².

- Corridors and staircases: often higher, around 3.0 kN/m² in many guidelines.

- Roof terraces may have lower sustained live load but may be checked for maintenance loads and water storage.

In design, the live load is applied as a uniformly distributed load on the slab, similar to dead load but with different combinations and factors.

Distributing slab load to beams: tributary width concept

Slabs act like plates or strips that transfer their loads to supporting beams along shorter or longer spans depending on whether they are one-way or two-way.

- In a one-way slab, most load travels in the direction perpendicular to the supporting beams on the shorter span.

- In a two-way slab, load is shared between both directions, and tributary widths for each beam are considered.

To convert slab load into line load on beams:

- Slab load (kN/m²) × tributary width (m) = beam line load (kN/m).

For example, if a slab has total load 7.25 kN/m² (dead + live) and the tributary width for a beam is 2 m, then the line load on that beam is 7.25 × 2 = 14.5 kN/m.

Load on beams and transfer to columns

Once slab and wall loads are converted to line loads, each beam carries:

- Dead load from its self-weight.

- Dead load from walls and finishes.

- Live load from slab (and possibly from partitions).

During structural analysis (manual or software), these line loads are used to find support reactions at beam ends, which are then treated as loads on columns. For preliminary hand calculations, the total load from connected beams and walls can be approximated to estimate the axial load on each column.

Estimating column and footing loads

Column load typically includes:

- Reactions from supported beams and slabs from all floors above.

- Self-weight of the column itself (usually approximated as a percentage of the total or computed from geometry).

- Any direct wall or point loads resting on the column.

Once the factored axial load on the column at foundation level is known, footing design begins. Footing load equals column load plus footing self-weight and a small allowance for soil overburden above footing level, and it is compared against safe bearing capacity (SBC) of soil to decide the footing area.

Influence of wind and seismic loads on low-rise homes

Wind load is calculated using IS 875 (Part 3) by determining basic wind speed, exposure, and pressure coefficients. For low-rise residential buildings (say up to four or five floors), gravity loads often govern design, but wind effects on slender or exposed structures and cladding cannot be ignored.

Seismic loads, on the other hand, can be critical even for G+1 or G+2 buildings in high seismic zones. IS 1893 uses the building mass (derived from dead load plus a portion of live load) to determine design base shear, which is then distributed along the height. This means accurate gravity load calculation directly affects seismic design forces.

Example: Load calculation for a simple G+1 residential room

Consider a 3 m × 4 m room in a G+1 building:

Assumptions:

- Slab thickness: 150 mm RCC with floor finish and plaster (dead load ≈ 5.25 kN/m² as previously calculated).

- Live load: 2.0 kN/m² for residential room.

- Total slab load = 5.25 + 2.0 = 7.25 kN/m².

If the slab is one-way spanning 4 m, supported by beams at 4 m spacing, tributary width for each beam is 3 m (full room width).

- Load per meter on main beams = 7.25 × 3 = 21.75 kN/m.

If a 230 mm wall runs along one beam, wall load ≈ 14.8 kN/m as calculated earlier.

- Total line load on that beam = 21.75 + 14.8 + beam self-weight (≈ 2.6 kN/m) ≈ 39.15 kN/m.

Beam reactions at each end depend on span and loading type, but roughly, for a simply supported beam of span 4 m with uniform load, each reaction is about half of total load. That reaction becomes part of the axial load on columns supporting the beam, which then accumulates with loads from upper floors and is finally carried by the footing.youtube

Common mistakes and practical tips

Typical mistakes include:

- Ignoring the weight of plaster, floor finishes, parapets, and water tanks in dead load.

- Using inconsistent units (mixing kg/m² with kN/m², or forgetting to convert thickness from mm to m).

- Assuming arbitrary slab thickness or live load without referencing IS 875.

- Not considering seismic loads where IS 1893 requires earthquake-resistant design.

Practical tips:

- Always start load calculation for residential buildings from unit weights given in the code rather than guesswork.

- Document each assumption (thicknesses, densities, live loads) clearly in calculation sheets.

- For detailed multi-storey design, use software like STAAD or ETABS but verify that input loads match your manual calculations.youtube

- For small projects, thumb rules can be used for initial member sizing, but they should be backed by at least one round of proper load calculation.

FAQs

1. What is the standard live load for residential rooms?

For typical dwelling rooms, many guidelines and references use about 2.0 kN/m² as imposed load, but the designer must check the exact value from the applicable live load code like IS 875 (Part 2).

2. Is wind load important for single-storey homes?

For compact, low-rise residential buildings, gravity and seismic loads generally control design, yet wind loads must still be checked according to IS 875 (Part 3), especially in high wind zones or exposed sites.

3. Can thumb rules replace full load calculation for small houses?

Thumb rules are useful for preliminary sizing, but safe and economical design requires proper dead, live, and (where applicable) wind and seismic load calculations consistent with IS codes.

Conclusion

Accurate load calculation for residential buildings is the backbone of safe and economical RCC design, from single-storey houses to moderate G+4 apartments. By understanding dead loads, live loads, and lateral loads, and by using IS 875 and IS 1893 as references, civil engineers and students can confidently estimate slab, beam, and column loads before detailed structural analysis. When these fundamentals are followed, the finished home not only looks good but also performs safely for decades.

Latest Articles

- 12 Common Mistakes in House Planning (And Smart Fixes)

- Bar Bending Schedule (BBS) – Basics with Example for Civil Engineers

- Cement Grades Explained: OPC vs PPC vs PSC (Complete Guide for House Construction)

- Types of Foundations Used in Residential Buildings: Complete India Guide

- House Construction Cost per Square Feet in India 2026: Complete City-Wise Guide