Designing a concrete mix for grades like M20, M25 or M30 often feels like balancing on a tightrope: increase cement and you get strength but lose economy, reduce water and the mix becomes harsh and unworkable. Medium strength concretes are used in most everyday beams, slabs and columns, so getting their mix design right can make or break both the quality and cost of a project. This guide walks through the major methods of concrete mix design for medium strength concretes and shows how the underlying logic is similar, even when the code names and charts change.

What is “medium strength” concrete?

In practical building construction, medium strength concrete usually refers to mixes with characteristic compressive strengths in the range of about 20–35 MPa at 28 days, such as M20, M25 and M30 under many code systems. These grades are common in residential and commercial foundations, beams, slabs and columns where durability and workability are as important as compressive strength.

Medium strength concretes sit between simple nominal mixes for lean applications and highly engineered high‑strength or high‑performance concretes. They need more careful proportioning than basic 1:2:4 mixes but are still broadly produced with conventional materials and equipment.

Core concepts in concrete mix design

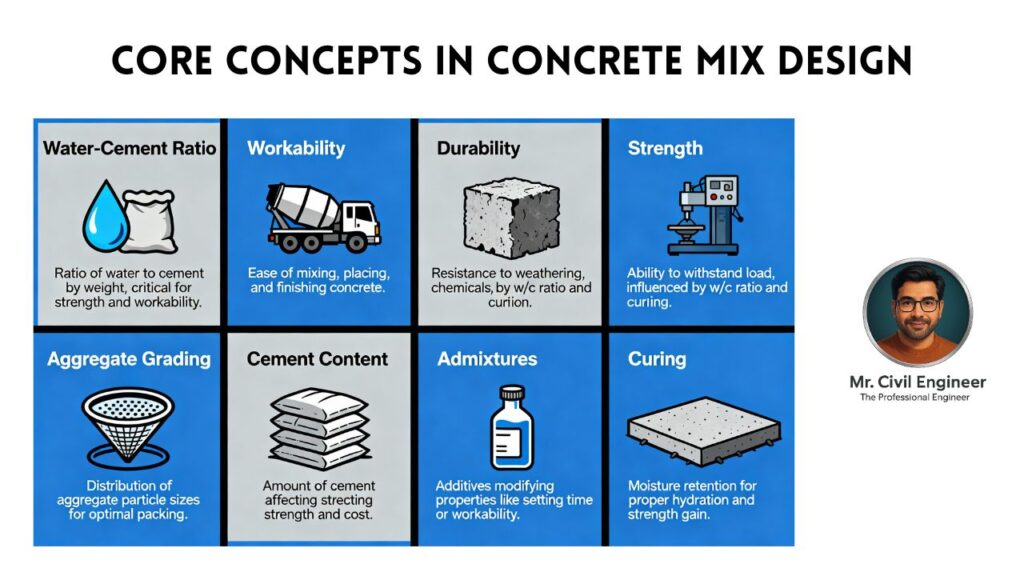

Before comparing methods, it helps to understand the key concepts that all of them share. The first is characteristic strength, typically defined so that only a small percentage (for example, 5%) of test results are allowed to fall below this value; from this, the designer calculates a higher target mean strength by adding a margin based on standard deviation and quality control level. This ensures that normal variability in materials, batching and curing does not cause too many failed tests in the field.

The second core concept is the water–cement ratio, which has a dominant influence on both strength and durability of concrete: lower w/c generally means higher potential strength and better resistance to aggressive environments, provided the concrete is fully compacted.

At the same time, higher water improves workability, so the designer must find an optimum balance, often using plasticizers or superplasticizers to increase workability without increasing w/c excessively.

Workability is commonly described using slump, compacting factor or Vee‑Bee time, with medium strength reinforced concrete for beams and slabs often designed for moderate slump ranges suitable for normal vibration. Codes and design guides provide typical recommended slump ranges for different placing conditions so that mixes are neither too stiff to compact nor too wet to segregate.

The general mix design procedure most methods share

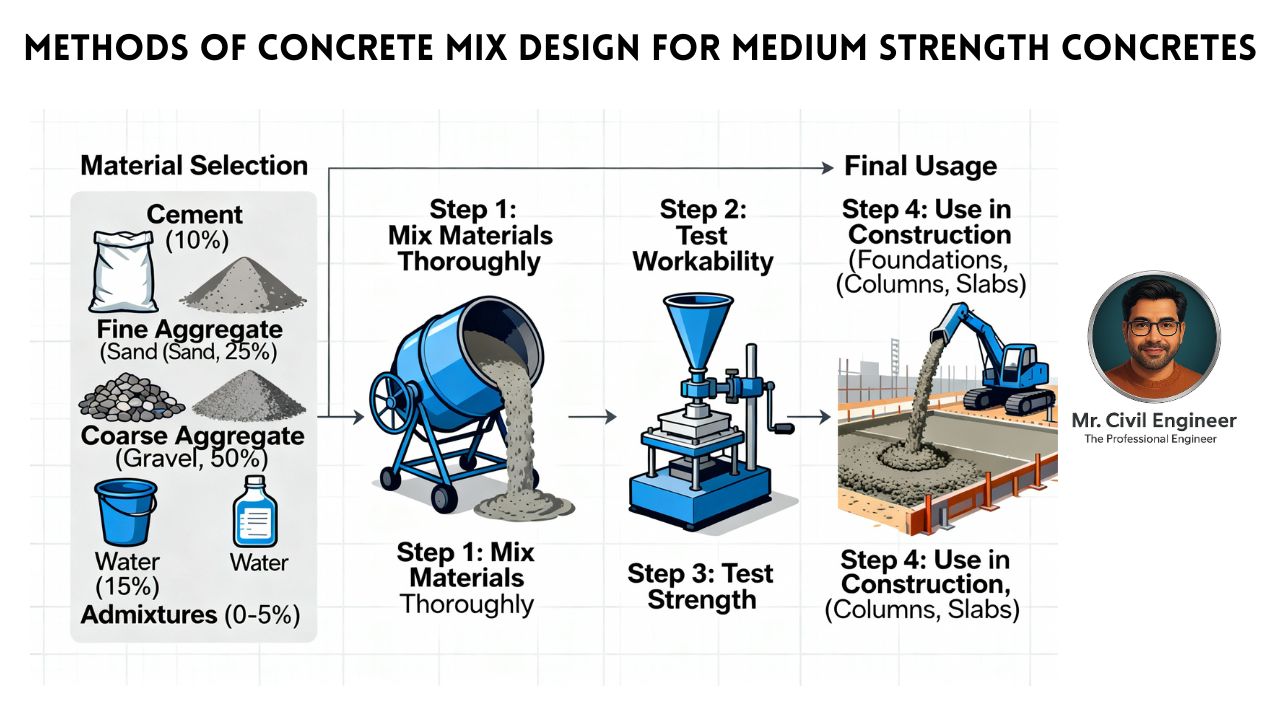

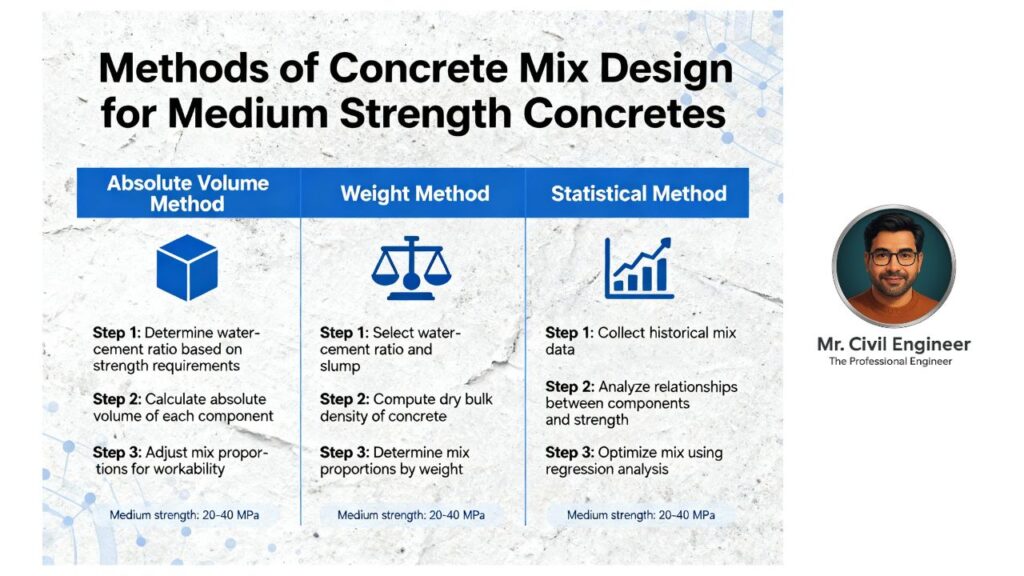

Even though different standards use their own tables and graphs, the high‑level procedure is strikingly similar. First, the designer selects the maximum nominal size of aggregate based on member size, reinforcement spacing and specifications, and then examines the grading of fine and coarse aggregates. Next, the target mean strength is calculated from the specified characteristic strength and an appropriate margin based on quality control.

With target strength known, a suitable water–cement ratio is chosen from code‑based strength–w/c curves or empirical relations, then checked against code limits for durability for the given exposure condition. After this, the required water content is selected to achieve the desired workability, using tables that relate slump, maximum aggregate size and aggregate shape to water demand.

Cement content is then obtained by dividing water content by w/c ratio, and verified against minimum cement limits in durability tables. Finally, the proportions of fine and coarse aggregates are fixed using charts or tables that consider aggregate grading, shape and workability, and the actual weights per cubic metre are calculated using the absolute volume method, which ensures that the sum of component volumes (cement, water, aggregates and air) equals the volume of concrete to be produced,

Trial and adjustment (trial-and-error) method

The trial and adjustment method is essentially an empirical approach in which the engineer uses repeated trials to find the most economical and workable mix that still achieves the required strength. It focuses on proportioning fine to coarse aggregates to minimize voids, often by filling a container with different layer combinations and lightly ramming to identify the combination that yields maximum density. Once a promising aggregate proportion is found, trial batches are made with estimated cement and water contents and cube strengths are measured at 7 and 28 days.

For a typical M25 concrete, an engineer might begin with a familiar base proportion, check slump and early strength, and then systematically adjust w/c ratio and cement content to move towards the target mean strength while maintaining acceptable workability. This method is straightforward and useful where sophisticated tabular data or software are unavailable, but it can be time‑consuming and heavily dependent on the experience of the engineer and consistency of local materials.

British DoE (Department of Environment) method

The British DoE method was developed under British Standards and has been widely used for normal‑weight concrete based on characteristic strength and target values for slump, air content, water content and cement content. It assumes that the designer chooses a target mean strength greater than the characteristic strength and then uses relationships between w/c ratio and strength derived from test data to choose an initial w/c value.

In this method, the required water and cement contents are obtained from tables that link desired slump, nominal maximum aggregate size and air content to typical water demand and minimum cement for durability. The fine aggregate content is then selected mainly as a function of maximum aggregate size and sand grading zone, while coarse aggregate content is calculated as the remainder to fill the volume. For medium strength concretes, the DoE method provides a structured way to balance strength requirements with workability and durability, particularly in regions that follow BS‑based codes.

ACI mix design method (ACI 211)

The ACI 211 method is one of the most widely taught and used mix design procedures, suitable for normal and heavyweight concretes up to about 45 MPa cylinder strength at 28 days, which comfortably covers the medium‑strength range. It is fundamentally based on the absolute volume method: the sum of the absolute volumes of water, cementitious materials, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate and entrapped air must equal the total concrete volume.

The ACI method typically follows these steps: select a suitable slump for the placing conditions; choose nominal maximum aggregate size; estimate mixing water and air content from tables; select w/c ratio from relationships with strength and durability requirements; calculate cement content from water content and w/c; estimate the required volume of coarse aggregate from standard tables that depend on aggregate size and fineness modulus of sand; and finally compute the fine aggregate content by subtracting all other component volumes from the total. For medium strength concrete, this method allows good control over both workability and durability, especially when combined with reliable local test data on aggregates and cement.

IS method of mix design (India)

The Indian Standard method, typically using IS 10262 along with IS 456, provides guidelines for designing normal (non‑air‑entrained) concrete mixes including both medium and high strength concretes. It requires input parameters such as characteristic strength, type of exposure, degree of quality control, expected workability, maximum aggregate size and specific properties of local aggregates. From these, the designer calculates target mean strength and chooses w/c ratio using strength–w/c relationships and durability limits.

Water content is selected from tables based on desired slump and aggregate size, after which cement content is derived and checked against minimum cement requirements for the specified exposure conditions.

The proportion of fine to coarse aggregate is obtained from tables that account for aggregate grading and workability, and final mix proportions are computed via the absolute volume concept. Comparative studies have shown that the IS method often yields relatively lower w/c ratios, and sometimes higher cement contents, which can enhance durability and strength for a given grade compared with some older approaches.

Rapid method of mix design using accelerated curing

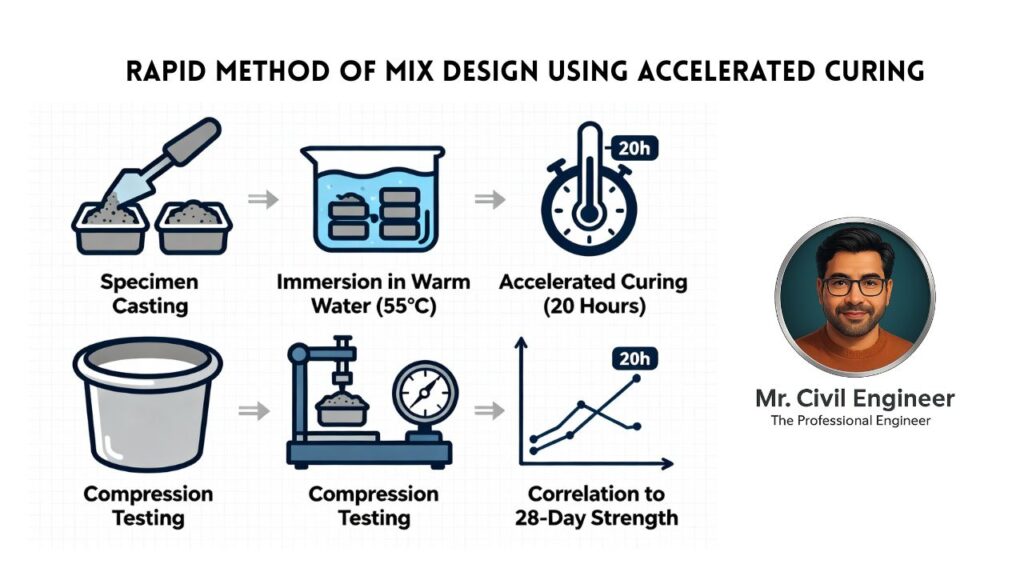

One challenge with conventional mix design is the time required to confirm 28‑day strength for each trial mix; projects with tight timelines may not be able to wait for multiple full‑cycle trials.

To address this, a rapid method using accelerated curing, developed by institutions such as the Cement Research Institute of India and standardized in IS 9013, can be applied. In this approach, 150 mm cubes of a reference concrete are subjected to a prescribed accelerated curing regime, and their accelerated strength is used to estimate the corresponding 28‑day strength.

Once a reliable correlation between accelerated and normal curing strengths is established, the designer can vary the water–cement ratio and mix proportions, test cubes after accelerated curing and quickly identify combinations likely to meet the target 28‑day strength. The rapid method does not replace standard mix design procedures but acts as a valuable tool for shortening the trial cycle, especially when optimizing medium‑strength mixes under project time pressure,

How do these methods compare for medium-strength concretes?

When comparing methods like trial and adjustment, British DoE, ACI and IS for medium-strength concretes, several patterns emerge. Empirical studies have noted that, for the same target strength, BS‑based methods may result in slightly higher water–cement ratios than IS methods, whereas ACI and newer IS procedures often recommend similar design parameters for certain strength levels. In many cases, the IS method tends to favor lower w/c and sometimes higher cement content than some older procedures, reflecting a stronger emphasis on durability.

From a practical standpoint, the choice of method is often driven by project location and code requirements: IS method is common in India, ACI is widely used in North America and many international projects, and British DoE principles appear in BS‑based specifications.

For typical medium‑strength structural members, any of these methods can produce satisfactory results if local material properties are correctly characterized and trial mixes are carefully evaluated.

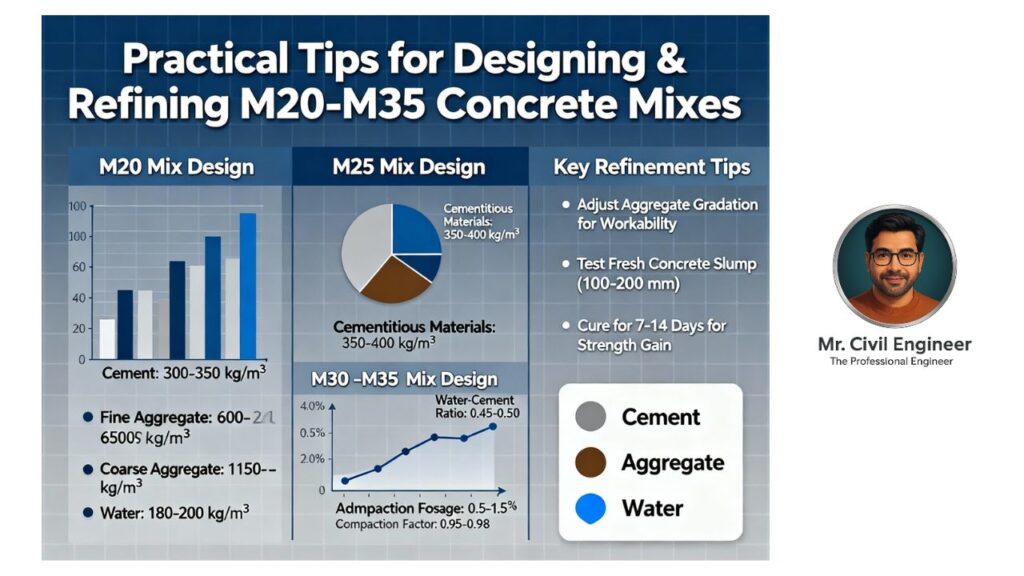

Practical tips for designing and refining M20–M35 mixes

Regardless of the method chosen, certain practical habits greatly improve the reliability of mix design. Always use up‑to‑date test data on aggregate grading, specific gravity, water absorption and dry rodded density, as these directly affect calculated volumes and water adjustments. For example, moisture in fine aggregates must be accounted for to avoid unintentionally increasing the effective w/c ratio.

It is also important to plan and document trial mixes systematically: record batch weights, slump, ambient conditions, compaction method and cube strengths at 7 and 28 days, and adjust the mix in small, controlled steps.

When better workability is needed, prioritize adjustments in aggregate grading and admixture dosage before simply adding more water, so strength and durability are maintained within design limits. This disciplined approach ensures that the theoretical advantages of any mix design method translate into consistent performance on site.

FAQs on concrete mix design

1. What is medium strength concrete in practice?

Medium strength concrete typically refers to structural grades with characteristic strengths around 20–35 MPa at 28 days, used widely in everyday beams, slabs and columns. The exact range may vary between code systems, but the idea is concrete that is stronger than lean mixes yet not in the high‑strength category.

2. Can nominal mixes replace design mixes for M25 or M30?

Many codes restrict nominal mixes like 1:1.5:3 to lower grades and require design mixes for M25 and above, especially in reinforced concrete where reliability and durability are critical. A proper mix design using IS, ACI or DoE methods gives better control of strength, workability and long‑term performance than fixed nominal proportions.

3. Which method is best for medium-strength concrete in India?

For projects governed by Indian standards, the IS method using IS 10262 and IS 456 is usually preferred, often supported by accelerated curing techniques when rapid feedback is needed.

However, principles from ACI or DoE may also be referenced in academic or comparative studies to understand how different approaches influence w/c ratios and cement contents.

4. How many trial mixes are normally required?

The number of trials depends on how well the initial estimates match the actual material behavior, but a small sequence of preliminary and confirmatory trials is common to fine‑tune workability and strength within acceptable tolerances. Using rapid methods can reduce the total time needed by providing earlier indications of likely 28‑day performance.

5. How do admixtures affect the mix design sequence?

Water‑reducing and super plasticizing admixtures allow designers to achieve required slump at lower water contents, effectively enabling lower w/c ratios for the same workability. In formal design methods, admixture effects are often incorporated by adjusting target water contents or by using specific guidance from manufacturer data combined with code provisions.

Conclusion: Choosing and mastering a mix design method

All major methods of concrete mix design for medium strength concretes—trial and adjustment, British DoE, ACI, IS and rapid accelerated‑curing based approaches—follow the same fundamental logic of targeting a strength, choosing an appropriate w/c ratio and balancing water, cement and aggregates by volume.

The “best” method for a given engineer is usually the one aligned with local codes, supported by reliable material data and applied with careful trial mixes and documentation in the field. By understanding both the shared principles and the specific steps of each method, engineers can design safer, more economical and more durable medium-strength concretes with confidence.